We live in an age where globally, on average, we have more democracy and more power to participate in change than before – teaching civics through entertainment could help us realize that power.

Written by: Anushka Shah

In the aftermath of the Great Depression and during the Second World War, there arose a new power in the late 1930s – the Action Superheroes. Fighting the bad and championing the good with their extraordinary abilities, Captain America, Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman were the start of the Golden Age of the superhero comics. In a time of destruction and incapacitated governments, these stories provided hope, diversion, and an enticing tale for reconstruction.

Over 75 years later, the superhero story remains one of the most popular narratives within the entertainment film industry. We may not be recovering from a war, but we live amidst corrupt governments, malfunctioning politics, and lumbering institutions. Superhero movies are incredibly entertaining not just by virtue of their spectacular special effects, but because they provide a seductive path for a better world – one that involves special powers over engaging in the messy complexities of reality.

This appeal of being able to find a solution outside of existing systems is tempting to mimic even in real life. We don’t expect superheroes, but we often visualize change in the form of getting rid of the current order or electing someone who promises to do so. Problems that bother us deeply are often the ones we think are too difficult to reform – and sometimes we may be right about that. Some systems are deeply unequal by design, as the Occupy Movement would say about Wall Street, and some governments are incapable of reform, as the Arab Spring protestors asserted about their authoritarian regimes – and problems like these do require insurrectionist actions if we are to create space for new structures.

But while insurrectionism can rescind or discredit existing systems, to build new ones and meaningfully strengthen them requires a different set of strategies. It requires what MSNBC commentator Chris Hayes calls in his book ‘Twilight of the Elites’, institutionalism. This is the belief that institutions can improve with structural change, and that reform rather than revolution is the way forward. Creating change in an institutional manner involves taking a strategic approach – it involves being familiar with organizations and authorities governing that system, identifying weaknesses and organizing collective action to bring attention to them, working with the ecosystem of participants to develop new solutions, and advocating change as a process rather than one-time action.

While civic engagement in the form of institutionalism does little to capture our imagination in the way revolution might, it’s essential to sustain any form of change. As activist and internet scholar at MIT Ethan Zuckerman writes, in the absence of a strategy shift following the protests, the Arab Spring in Libya, Syria and Egypt toppled dictators but soon ensued into carnage and chaos, and while the Occupy Movement succeeded in bringing inequality into conversation, it failed to create lasting structural change. Change is not limited to legal or political reform, but as Lawrence Lessig writes, includes affecting economic markets, social norms, and technology. The strategies are multiple, and the actions available towards institution building, abundant.

The problem with institutionalism is two things – first, we have low trust in institutions and their actors, and second we have little knowledge about them. Various studies show a decline in civic participation and trust in governments globally[1], and hardly anywhere does formal education involve the meaningful illustration of ways to participate in the systems we learn about[2]. In an investigation about how Americans think about government, the Frameworks Institute found that the respondents had little understanding of the distinction between private and public, governance and politics, and could not distinguish functions of public institutions[3]. In order to improve institutional trust, the institutions need to improve, and for the institutions to improve, citizens need to engage, monitor, and participate.

At the 2017 inaugural summit of the Obama Foundation in Chicago, former President Obama said – “The moment we’re in right now, politics is the tail and not the dog. What we need to do is think about our civic culture, because what’s wrong with our politics is a reflection of something that’s wrong with the civic culture, not just in the United States but around the world.”

So, how do we go about creating knowledge and motivation around civic engagement? And how do we make an approach of institutionalism as enticing as it’s sexier counterpart, insurrectionism? Because the thing with institutionalism is that while it’s important, effective, and urgent – it can also be incredibly boring. It involves learning systems and strategies rather than rejecting them, creating change part by part rather than in one swift action, and being patient about results as opposed to seeing rapid change. It can’t compete with the bravado of insurrectionism, which is bold, clean, and direct in its action-to-result logic.

Let’s go back to the superhero movies, or the narratives that fiction can offer. During World War II, entertainment didn’t only play a role in giving audiences escapism, it was also a powerful tool of propaganda for governments on both sides. Pure entertainment in the form of oral storytelling and performance arts, or then movies, television, and radio content has been used since time immemorial to carry political thought, historical accounts, and social messages. At the core of it, when we’re being entertained, our defenses are down as we’re not conscious of being preached to. We applaud the thought and behavior of characters we admire, and admonish those of the ones we despise.

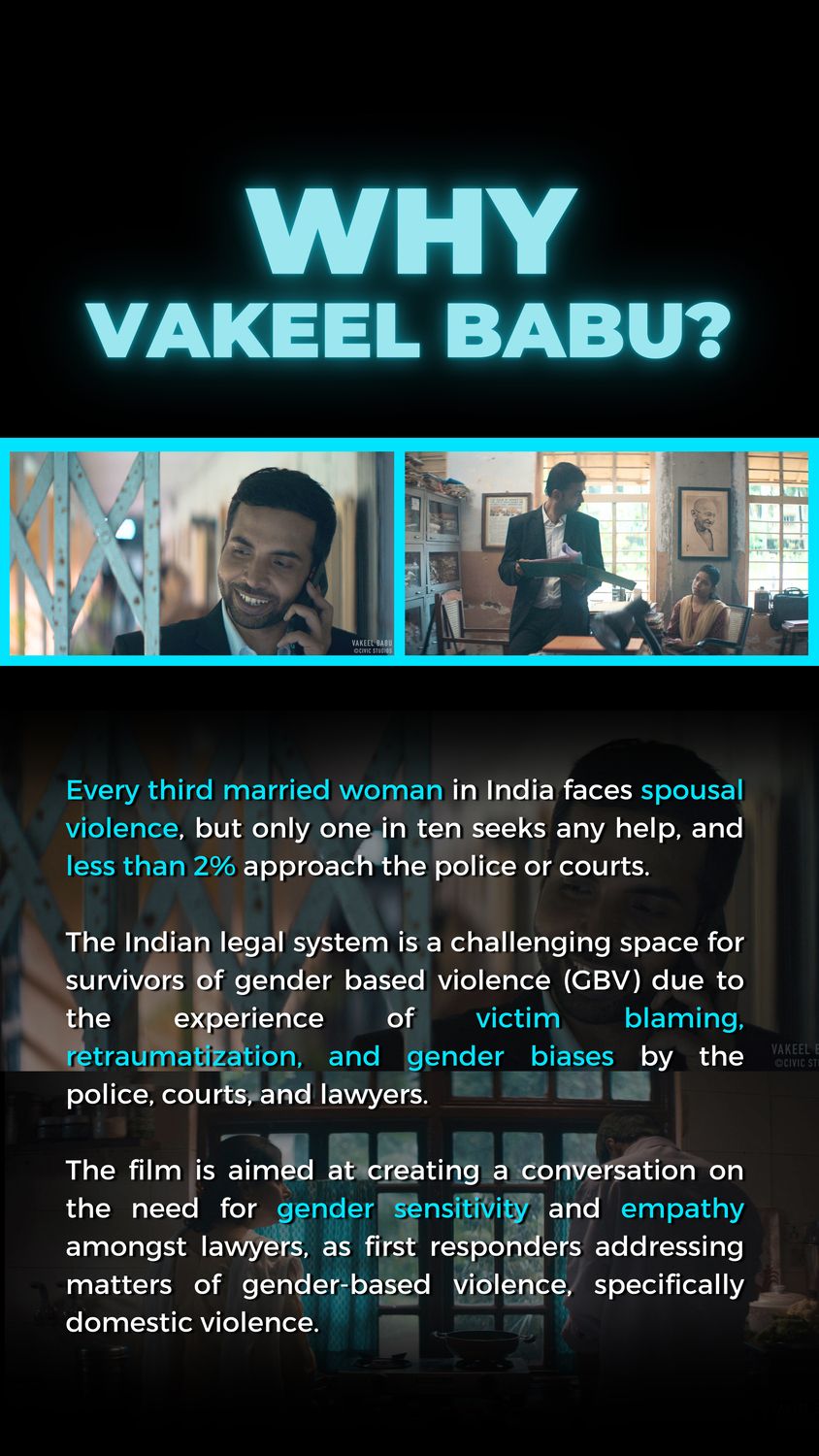

Studies attempting to measure the effects of entertainment show that sometimes these influences are strong enough to shift the needle of our own beliefs or behaviors. Betsy Paluck, a Princeton psychologist and winner of this year’s MacArthur “genius grant”, showed how a radio soap opera in post-genocide Rwanda was able to decrease prejudice[4]. An Indian soap about sex-education has become one of the most watched shows across the world with over 400 million regular viewers – the show’s impact reports show significant evidence for changes in family planning methods amidst viewers[5]. More popular examples of entertainment designed for influence are shows like Law & Order, Sesame Street, Captain Planet, Numb3rs, or then movies like Spotlight, Lincoln, The Help, or Contagion (produced by Participant Media whose goal it is to produce entertainment with social impact).

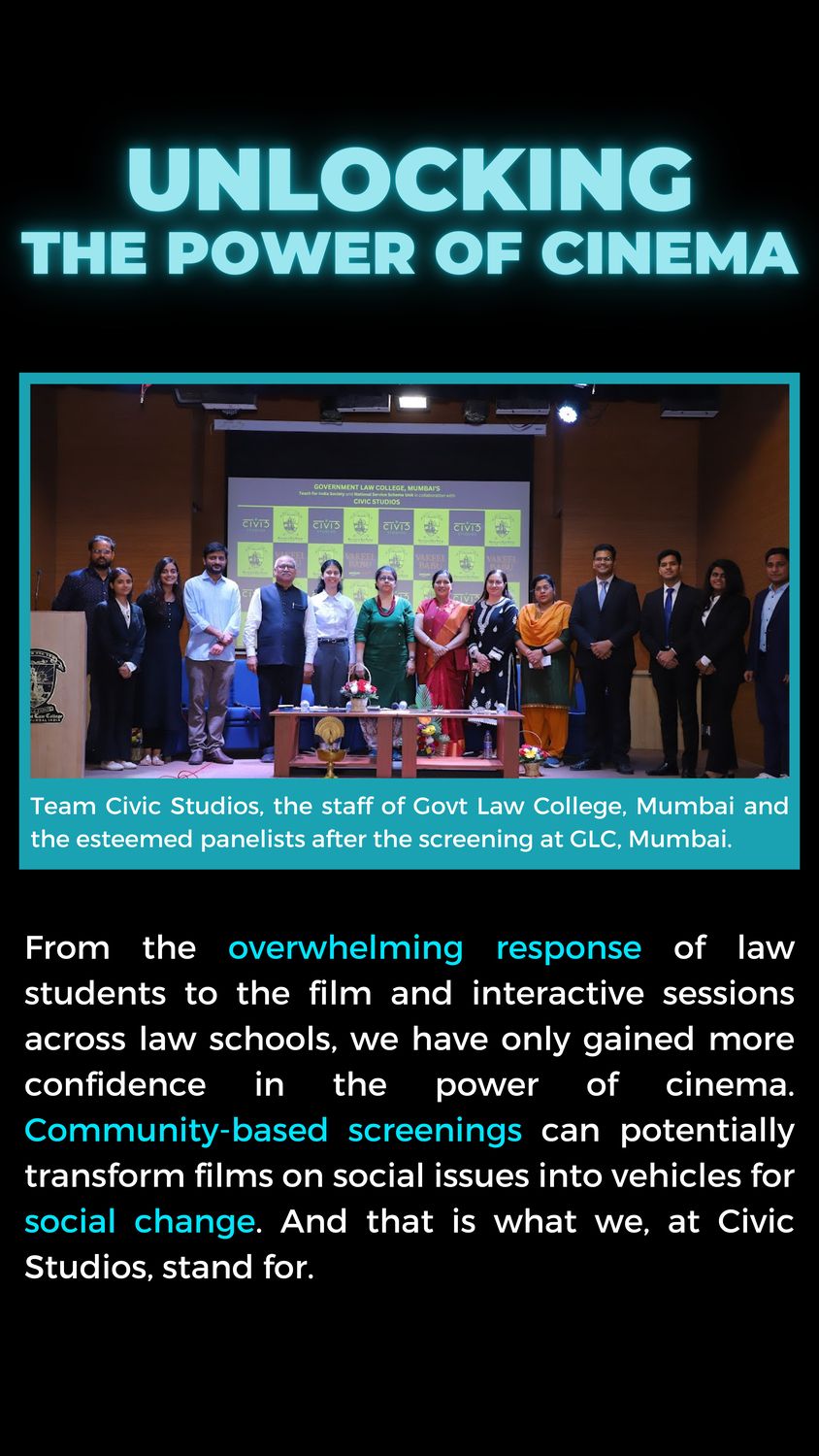

Entertainment’s ability to both amuse and influence affords an important contribution to the cause of democracy – the potential to model civic engagement. Humor, drama, and other elements of entertainment can do things like bring to our attention an issue we might have little care or knowledge of, explain a complex policy or how an institution works using an engaging narrative, give us a protagonist to help us live the experiences of groups and minorities that we might otherwise be emotionally distant from, or then bring to the forefront strategies and stories of activists, community organizers, and leaders from the field. It could also allow us to imagine inventive ways of organizing and governing ourselves, in the way (good) science fiction does for technology and innovation.

The possibilities are many, some of which are commonly used in art and film and some of which are untapped, but much of which can give power and appeal to the idea of institutionalism. This not about replacing superhero movies – we will always need those and should enjoy their freedom from reality – rather, this is about evolving and expanding the purposes of entertainment. We live in an age where globally, on average, we have more democracy and more power to participate in change than before – teaching civics through entertainment could help us realize that power.

[1]https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/07/trust-institutions-trump-brexit/489554/

[2] Peter Levine, professor of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Tufts University, makes the argument that the subject of “philosophy addresses the nature of justice but not actions that might be available to you to make the world most just”, political science is about the study of government and politics, but not “what you and I should do together”, and professional schools may teach us how to be lawyers or policy-makers, but “no department teaches strategies for citizens”.

[3] ‘how to talk about government’ paper